I’ve moved Historically Us to a new location! You can now find me at http://historicallyus.com . I will migrate subscribers and make this version of the site private in a month or two. Hope to see you at our new location!

Podcasts as Public History

This week’s blog assignment included listening to at least one podcast from BackStory Radio, and one episode from either Journal of American History Podcast, BBC’s In Our Time Podcast, Exploring Environmental History Podcast, or Nature’s Past Podcast. After listening to these, we were instructed to reflect on how history is presented differently through these podcasts versus other forms of media we have explored throughout the semester.

Personally, I love a good podcast. Growing up we always had the small radio in the kitchen tuned to NPR, listened to Car Talk on Saturday morning drives, and, once podcasts came around, I listened to the Leaky Cauldron’s PotterCast at my first job at the public library. As an adult, my car radio rarely leaves NPR and I still love a good podcast binge.

As it happens, in the past few weeks I’ve been on a weekend road trip back to my hometown and have been doing some deep winter cleaning; both perfect opportunities for enjoying a podcast or five.

You might say these podcasts are nearly purrfect. *ducks*

While on the road, I listened to episodes from the JAH podcast, BBC’s Our Time, Exploring Environmental History, and caught up on the latest Digital Campus episodes. Throughout the week I also listened to quite a few different BackStory episodes. These podcasts represent a wide variety of topics, reflective of just as much diversity as any one history department’s list of courses on offer.

Indeed, many have argued that the digital realm provides a better platform for distributing information on subjects, like many of our favorite sub-fields of history, that fall on the long tail. This is an idea we have seen reflected in the readings we’ve done and the projects we have examined over the semester.

The wide reach of the internet makes it possible to engage multiple audiences and share good, trustworthy, informative history on a large variety of topics.

For instance, when considering the podcasts we listened to, it seems there are a number of different target audiences for the different programs.

First, of course there are the likely differences in audience that the topics of each podcast might attract. For example, the few episodes I listened to featured guests and stories that cover American, Egyptian, ancient, modern, environmental, Native American, economic, and educational histories.

Looking a bit deeper though, there seems to be differences between the podcasts produced primarily for an academic audience or for a wider public audience. Podcasts from the Journal of American History and Exploring Environmental History did feel like they had a more academic bent. These programs were longer form with one topic and one guest. They expect that the listener will remain engaged by a deeper understanding of one particular topic or work.

I will find the time, Sweet Brown. Still, an hour’s worth of information on one topic, with one speaker, can seem more like a lecture or a keynote speech than a podcast.

In contrast, podcasts like BackStory and Our Time follow a more conventional public radio format. Of all the podcasts, BackStory was far and away my favorite, partially because it follows such a familiar structure. This structure consists of several different stories based around a broader topic; reminiscent of popular shows like This American Life, Snap Judgement, and Radio Lab. If the goal is to engage and inform a wider public audience, this format seems to fit the ticket better, in my opinion. The shorter stories allow for a listener to engage for smaller bursts of time; if they don’t find one story as interesting they can simply wait for the next; and, if the show appears on the radio as BackStory does, listeners just tuning can easily enter the program without being lost.

When compared to other forms of digital media we have examined, it seems that the podcasts across these categories are most akin to broad topical blogs. Unlike a digital archive with a wealth of primary materials to dig deeply into or a digital project with an explorable narrative, podcasts offer bite-size jumping off points into history. We’ve also read about the decreased willingness or capability to read long form written narrative; podcasts offer a way to connect with audiences who would be less likely to read long-ish form writing in blogs, articles, or books.

Overall, I think podcasts are yet another great tool in the digital toolbox as it relates to engaging new audiences with historical information. This is especially true with programs like BackStory that appear not only online, as a podcast, but also on the radio.

Going “Bananas” in Digital Archives

This week we are taking a look at different digital archives and thinking about what they might offer over traditional print archives, how they are structured, and how their design/functionality might be improved.

After clicking around a few of the archives I was intrigued by the Prelinger Archives. This archive represents a collection of “ephemeral” films initially collected by Rick Prelinger. While a physical location and collection still exists, most of the archive is now available online through the Internet Archive. A majority of the items in the collection are a part of the public domain and can be used in whatever manner the user chooses. (It should be noted, however, that the Internet Archive will not give written permission for any particular film or clip to be used, rather, Getty Images serves as the collections “stock footage sales representative.” This means that, for a fee, Getty will give you a license to use clips from the films in the Prelinger collection that will protect you against any copyright infringement claims.)

This collection strikes me as especially useful in a digital form because of the nature of the items; that is to say, films ranging from the turn of the twentieth century through to the present day. On a digital platform, these films can be presented to researchers in a number of formats that do not require the use of a wide range of hardware, no physical travel is required, and the large physical space necessary to store so many films can also be minimized. Another benefit is that the digital format presented online allows for the videos to be cleaned up and and any damage repaired.

Let’s turn to the interface of the Prelinger’s online home. The design is fairly simple; bordered areas of text contain information about rights, the history of the archive, and a forum section for user interaction. There are various routes to accessing the materials themselves; there is a list of items alphabetically, there are sub-collections, lists of “Staff Picks,” “Most Downloaded Items Last Week,” and “Most Downloaded Items.”

This last list, “Most Downloaded Items,” goes a long way to show the impact and traffic the site has. The most downloaded film is About Bananas. This is a 1935 film, commissioned by the United Fruit Company, to inform people about the process of growing and shipping bananas. About Bananas has been downloaded nearly 27 million times.

(The clip above is the same film uploaded to YouTube, where it only has 171 views.)

Clearly, with that many downloads, About Bananas appeals to a variety of users of the archive. A historically-based research and writing project could easily use About Bananas as a central piece of primary evidence. For instance, a project considering the impact of Western owned agricultural firms on the environment and culture of Central American countries during the first few decades of the twentieth century. Because the film is silent, it could be creatively used alongside music of narration in a documentary on the banana industry or Central American-United States relations.

Alternatively, a comparative approach might use About Bananas along side another film from the Prelinger Archives, the 1945 US Government produced Emergency in Honduras.

While About Bananas is basically an ad for Americans to buy bananas, Emergency in Honduras shows the perils of dependence on the banana when war interrupts shipment of the fruit. Both films, however, portray an image of money and intelligence from the United States swooping in to save Central Americans through labor jobs, first in the banana fields and then through public works projects that speed the production and export of war-time goods instead of bananas.

Using these two films together creates a unique view of Central American-United States relations through two specific moments in time. By using keyword tagging, the user can easily see a link between the two films that might otherwise be in different sections because of their age, their creators, etc.

I like the tagging and the other forms of navigation through the Prelinger archive. The only thing that confused me was the “Related Collections” section of the home page. I wasn’t sure if these items were other sub-collections within the Prelinger or whether they were totally separate. Thinking they were a part of the Prelinger archive, I spent quite awhile looking at drive-in movie theatre intermission ads; but, after a second look, I don’t believe that collection is a part of the Perlinger so I moved on to other items.

A means of improving the value of the online archive, to academics at least, would be to add more detailed information about the films. The downloadable metadata does not include year, location, or any sort of Dublin Core level data. The metadata does, however, contain information like keywords, description, rights, date uploaded, and title.

Haunting Hoaxes, Frightening Forgeries, and Angsty Alterations

Unfortunately, this isn’t really a Halloween-y post, but the topic can get a bit spooooooky. OK, I’m probably stretching it, but I’m in the Halloween spirit, sorry ’bout it.

This week we are considering digitally altered or forged sources. We’ve read a few articles and looked through some galleries of fakes to get a grasp on what can and is being done in the world of digital trickery.

I’m pretty inexperienced when it comes to spotting a Photoshopped image. When it comes to images in popular magazines or advertisements, I assume they have been touched-up, at the least, and probably contain some slimming, tucking, and lifting many times.

For some reason, however, I’m less apt to think about the same types of manipulation when it comes to news photographs and even less so with historical images. As far as images in the news media go, I should definitely be less naive. Luckily for me, there are often internet sleuths who swoop in to debate the integrity of an image.

As for the historian in the digital age, I feel like there isn’t much more to be worried about than in the past. “A search for historic image forgeries” tends to bring up photos of fairies and ghost, some with misleading captions, and even a super creepy looking fake baby Adolf Hitler.

Most of these forgeries were done at the same time the photo was taken, and they are usually easy to spot with the modern eye. But there are historic images that have been edited in our time, like in-a-gadda-da-oswald, though many of these are easy to spot as well.

I don’t really see the evidence of any major modern historical hoaxes or forgeries. That isn’t to say that historians shouldn’t be aware that it could happen, but even in the digital age we generally get our primary material from institutions that we trust. Images from the National Archives or the Library of Congress should be trustworthy, although the historian must still keep an eye out for manipulation contemporary with the image’s creation. The problems will arise for historians of our current time, when they have to sort through all the digital alterations and distinguish between cosmetic, malicious, and playful changes that have been made.

One of the pioneers of digital photography forensics is Hany Farid. After reading several articles with quotes from Farid and checking out his blog I’ve picked up a few things to keep in mind when examining an image for potential tampering. At the most technical level, Farid uses specialized software he has created to find any digital artifacts that indicate a forgery. However, there are less technical means of spotting giveaways.

For instance, shadows play a major role in authenticating an image. Another potential give away is color consistency; if the colors or the clarity of certain parts of the image seem different than the majority of the image then portions may have been added or parts may have been heavily retouched. This seems especially true in historic photos. In cases where people have been painted out of the image or dancing fairies have been added in, it is clear to see the inconsistency if you look close.

In sloppier cases, even modern Photoshoppers will leave the evidence of their changes in plain view, causing us to not only laugh, but also reconsider just how often the images we see have been manipulated to present a specific ideal.

In the modern age, whether we have our historian hats on or not, we have to be mindful of potential tom-foolery. It is encouraging to imagine, however, that historians may have a leg up as we are trained to examine all sources with a critical eye. Undoubtedly, however, there will surely be some altered images that will slip past even the most critical eye.

Tom Hitchcock on Social Media and the Humanities

A rather inspiring post from Tim Hitchcock, Professor of Digital History at the University of Sussex, discussing the usefulness and importance of digital methods of communicating humanities work, research, teaching, etc. Hitchcock also discusses the benefits of early career scholars establishing an online presence that is both professional and true-to-life. Some of my personal favorite excerpts:

“By building blogging, Twitter, flickr, and shared libraries in Zotero, in to our research programmes – into the way we work anyway – we both get more research done, and build a community of engaged readers for the work itself. We can do what we have always done, but do it better; as a public performance, in dialogue amongst ourselves, and with a wider public.”

and

“Twitter and blogs, and embarrassingly enthusiastic drunken conversations at parties, are not add-ons to academic research, but a simple reflection of the passion that underpins it.”

You can read the full post here. (The version of the article I saw shared via Twitter was on the London School of Economics site [located here if you want to go that route] but I’m favoring the link directly to Hitchcock’s website.)

Copyright and Access in the Digital Age

With it being Open Access Week articles, tweets, and livecasts about issue of access, copyright, and sustainability have been taking place across the web. One of my favorites was the New Yorker article by Louis Menand, “Crooner in Rights Spat: Are copyright laws too strict?.”

Coincidentally (or not, Dr. Shapiro?) we are considering copyright issues in our readings and discussion this week. The first thing that stands out is the similarities between Menand’s 2014 article and the videos, interviews, and articles we’ve been assigned from the aughts (2001-2008 in this case).

Free buttons, cookies, and intellectual stimulation where on offer at the live stream of the opening OA week festivities at our library.

Just as previous articles have discussed the STEM fields’ early adoption of many digital aspects, we see STEM fields moving forward with more expansive open access than the humanities Indeed, much of the discussion occurring around #OA2014, and open access in general, is focused on the sciences.2 Of course, making scientific findings available as widely and rapidly as possible has potentially life-saving, and more easily measured, implications. On the other hand, the impact of humanist research is a bit more “squishy,” to put it in highly technical terms.3

What I appreciated the most about Siva Vaidhyanathan’s introduction to Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual property and how it Threatens Creativity was the insightful consideration of creative (humanist, I would argue) contributions to an openly accessible world. Vaidhyanathan summarizes John Dewey’s “thin” copyright arguments for encouraging a strong public sphere that ensured “(t)he public should be better educated to be able to distinguish between solid description and mere stereotypes” that were popular in the media of the time.4 Vaidhyanathan argues that copyright restrictions have thickened as time progressed and corporate interest, like those of the movie industry, have secured stronger control of the creative public sphere; he also rejects the idea that creative works should be discussed in terms of “property.”5

“Remix” seems to be quite the buzzword within this discussion. In 2008 Lawrence Lessig discussed the modern remix culture on Terry Gross’s *Fresh Air* following the release of his book Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. Lessig argues that just the act of creating a copy can no longer be the basis for legal restrictions; rather the intent, the extent, and the economic implications should be weighed more heavily. If someone is building on, using, or remixing the creations of others, Lessig believes there should be no legal restrictions. Indeed, many historical examples show how the public creative and intellectual sphere has often been a cultural palimpsest of sorts.

Lessig is well known for founding Creative Commons, a non-profit organization that advocates for copyright reform.

(From a history standpoint, it was a real eye opening moment to hear Lessig discuss the Founding Fathers specifically protecting the freedom of press, despite the fact that the press at that time was often explicitly biased and sketchy at the best of times, and compare that historical form of press to modern blogging.)

In consideration of the academic, specifically historical, realm, Roy Rosenzweig points out the argument that works born out of publicly funded institutions should be available to the public that did the funding.6 Rosenzweig lays out six options for going fully or partially accessible. After considering each option, it is clear that while adapting to a new technological reality requires thoughtful discussion and debate, it is possible to adapt in a positive way that creates cultural or monetary value for companies, academics, and the public. Lessig also discusses the potential for commercial entities to find new ways to get monetary value out of “free sharing activity.”7

I’m personally persuaded by the arguments in favor of “thin” copyright restrictions and more open resources in the academic world specifically. Beyond the statistical facts that open research is cited and viewed more, I prefer the concept of a more open and beneficial exchange of insight and knowledge.8 I prefer the vision of copyright as an incentive for artists to continue creating valuable work. Still, I’m too ignorant of all the changes that have been made between these pieces and the more current developments of copyright and open access and there is plenty more to be learned.

[begin not-strictly-assignment-related-addendum]

While copyright is, sensibly enough, one of the biggest issues up for discussion, I’ve also seen some really interesting posts and comments regarding queer archives and accessibility. Issues that arise in this realm often have more to do with cultural constraints or privacy concerns, as opposed to a strictly legal copyright issue. Whitney Strub published a blog post this week entitled “Queer Sex in the Archives: ‘Canonizing Homophile Sexual Respectability’” that reflects on an Oct. 2 talk from historian Marc Stein. The talk, and the well written article, examine why publications like Drum, a more unapologetically erotic queer publication, are missing from both scholarly works and archives.

Stein’s talk was a preview for his article, “Canonizing Homophile Sexual Respectability: Archives, History, and Memory,” which was published in the Radical History Review‘s special edition “Queering Archives: Historical Unravelings” on October 23, 2014. While the whole issue appears to be full of intriguing articles and could constitute an entirely separate post, I’ll end on one final observation; the *Radical History Review* is behind a pay wall, inaccessible to radicals lacking the proper affiliation.

[/end not-strictly-assignment-related-addendum]

1. For example, at the screening of the opening panel (hosted at Atkins Library ) I was struck by the fact that nearly all of the panelists worked strictly within science related fields.↩

2. In his Fresh Air interview, Lessig addresses the same issue of priority in having STEM related research open to other researchers. ↩

3. Vaidhyanathan, Siva. Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual Property and How It Threatens Creativity. New York: New York University Press, 2001. 7.↩

4. Ibid. 15.↩

5. Rosenzweig, Roy. “Should Historical Scholarship Be Free?.” Vice President’s Column. AHA Perspectives. April 2005. Available at http://chnm.gmu.edu/essays-on-history-new-media/essays/?essayid=2↩

id=”fn6″>6.Gross, Terry. “Lawrence Lessig’s ‘Remix’ For The Hybrid Economy.” Fresh Air. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: WHYY, National Public Radio, December 22, 2008. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=98591002.↩

7. Vaidhyanathan, Copyrights and Copywrongs. ↩

THATcamp Piedmont 2014

This Saturday I attended my first THATcamp and it was amazing! The inaugural 2012 THATcamp Piedmont was hosted at Davidson College, in Davidson, North Carolina, and the 2013 event as held at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. This year THATcamp headed back to Davidson.

Before the actual morning, there were several known workshops, a Hackathon that would go throughout the day, and one suggested session. As promised, on Saturday morning a diverse group of impromptu sessions filled out the schedule further.

One way THATcamps remain similar to traditional conferences is the inevitably difficult decision of which session/workshop/event to attend. THATcamps overcome this difficulty in a way that traditional conferences have not. A page has been created for a large portion of the day’s sessions and linked to the primary schedule on GoogleDocs. (Schedule can be found at tinyurl.com/thatcamppmt) Through this connection of files I can see not only notes, sites, and cites for the sessions I attended, but also notes for those I wasn’t able to hear.

The sessions/workshops I attended in the flesh were informative, inspiring, and fun. In the first session I learned about using Neatline in Omeka to create multi-layered maps. Anelise H Shrout shared Neatline examples with us, then got us going on Omeka.

Next I attended a session guided by Mark Sample and Kristen Eshleman on the “Domain of One’s Own” project. While the session definitely provoked some feelings of jealousy directed at the students who are given a domain name of their own through their universities, it also inspired me to look into Reclaim Hosting and sign up for my own domain! (You can expect this blog to eventually make the move to a new address once I figure out how everything works)

After a delicious lunch I got to play around with Snap!, the programming language/tool from UC Berkeley that allows you to build code using blocks that snap together. Raghu Ramanujan was a great instructor through our experiments with Snap! and we managed to get our “sprites” to draw shapes and play tag by the time the workshop was over.

The final session I attended was led by Fuji Lozada and focused on social networking. Fuji asked us all to put our name on a piece of paper and list the three people in the room we talk to the most, he then entered that data into an Excel sheet that was plugged into the UCINET program. Voila! A simple and small social network emerged from our answers. We also looked at several different sites like WolframAlpha, Immersion, and TagsExplorer which offer different types of networking analysis.

In this short recounting I’m leaving out lots of other info that was shared, discussed, and pondered over. The long and short of it for me is that I was exposed to many different tools, resources, and methods that I was not familiar with. The day especially made me rethink the potential for my own thesis. Tools like the DH Press WordPress plug-in made me see the potential for creating a visually inspired narrative about some of the Antebellum Charlotte women I study. (DH Press was also another reason I decided to go ahead and sign up with Reclaim, as I want to play around with this very cool tool to better understand the possibilities.) I left the beautiful Davidson campus feeling inspired and energized and for that, I think the organizers of this years THATcamp Piedmont!

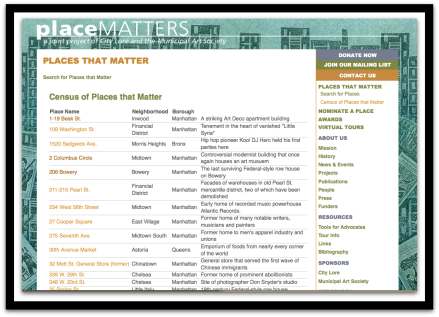

Place, Space, Memories: City Lore

BLOG ASSIGNMENT: Examine the City Lore website, focusing on the “Place Matters” section, which includes several walking tours and a census of places. Post your response to the site, considering how, through the census of places and walking tours, these projects contribute to fostering a sense of place and memory on the urban landscape through digital media. Consider it in light of other projects we’ve examined during the semester.

According to their “About” page, City Lore‘s mission is “to foster New York City – and America’s – living cultural heritage through education and public programs.” As an activist organization interested in preserving the urban landscape in an effort to preserve the memory and history of New York, City Lore has turned to a digital platform to engage with the communities they seek to work with. Their site is also meant to serve as a “living archive” of the city’s history and has received funding from NEH to fulfill these goals. The following quote particularly struck me.

One of the primary features of Place Matters is the Census of Places that Matter. The Census features an extensive list of locations with descriptions and pictures. The descriptions explain what the place is, where it is, and why it is uniquely important. The places listed have been “nominated by the public because they connect us to the past, host longstanding community and cultural traditions, or make the city distinctive.”

Community members can easily nominate places through a form on the site. The form requires the name of the place, a description, and the first and last name of the user. There are a number of other pieces of information that can be filled out as well such as the physical details of the place and plans or threats to a location. Users can also make comments on places that have already been nominated by others.

The ability of the public to contribute to the list of places that matter is vital to the mission of the organization to engage and work with the community. Judging by the hundreds of places listed on the Census, the project is extremely expansive and successfully engages people to contribute.

The Place Matters site also features a selection of “virtual tours.” These tours are in the form of a slideshow or booklet. Some are quite short, while others features dozens of “pages” of information and images. While the project, as we are examining it, is within a digital space, it encourages the user to explore the physical space as well. The tours do not attempt to use a street-view style tour of the locations, that would potentially replicate a tour in the real world. In fact, the site provides a detailed page of information on different tours and tour guides in the city.

The virtual tours featured on the site, six in total, explain how the story of relatively small geographical spaces can be representative of the history of the city as a whole. The “Seeing East 4th Street: Vernacular Architecture in New York City,” for instance, follows the history of the street early projects of speculators to create row houses for the from merchant class to the wave of immigrants and the Panic of 1837 that inspired landlords to repurpose single-family homes into multi-family housing.

These changes are representative of the history of New York as a whole as it expanded in the early part of the nineteenth century and then boomed as large numbers of diverse immigrant groups moved in. Other tours follow artistic movements in different neighborhoods, creating connections between old and new residents and art forms.

The guides use relatively short blocks of text along with large images to give both a visual and intellectual understanding of the evolution of each space. Through historic images, the site provides a visual representation of the memory of a location. The images serve to further reinforce the lesson that each piece of the urban landscape has a history to impart to us in the present.

The tours not only offer a better understanding and sense of history of the physical space they focus on, but also give the reader the tools to interpret the meaning of other spaces. Reading through one of these before going on a physical tour of the location would help someone know what to look for and how to interpret it.

For someone (like myself) with no training in interpreting urban landscapes, providing this information is vital for a fuller appreciation of what a physical space can tell us. “Seeing East 4th Street: Vernacular Architecture in New York City,” in particular, teaches the reader how to see the history represented by the architecture and geography of one block.

City Lore effectively uses digital tools to convey the meaning behind the historic urban landscape, connect memory with space, and create a connection between the community and an organization determined to preserve the past. I very much enjoyed exploring the site and I can see using it as a visitor to New York for AHA 2015.

Decisions, Decisions, Continue!

Since my last post I have been doing a few things with my digital project. First of all, I spent some time playing with the CSS on the university-hosted version of Sentimental Locks. The university-hosted site only has four potential themes to choose from. Some of the colors can be customized within each theme, but there are only a few color choices per element. So, I found a helpful video showing how to use the Firebug plug-in for Firefox to isolate various elements, see what they would look like in different colors, and then make the necessary additions to the style sheet. The results were minor in the grand scheme of things, but they felt like a victory none the less and I learned a thing or two along the way.

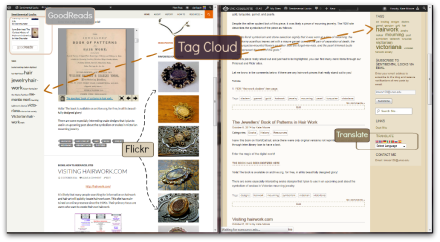

Still, the site was looking quite bland. On the other hand, my WordPress.com version was looking a little empty as well. I had already added several different social media widgets to my WordPress.com site, but I hadn’t set up the necessary accounts to connect it to. I went about doing that and the site started to look much more like I had imagined.

I want the project to serve as a central point connecting disparate resources and pieces of media from around the web, and these social media widgets are a necessary tool to achieve that end.

Unfortunately when I popped back over to the U-hosted version I realized that hardly any social media widgets were available.

Specifically, I wanted Twitter, Flickr, Pinterest, and GoodReads widgets. From browsing around the web I know that most people have a visual interest in hairwork; you can find many images on Pinterest and Flickr, and I wanted to tap into these resources to include plenty of visual elements. I wanted to include GoodReads as a way of connecting those who may have seen images of hairwork with traditional print media (both popular and academic) that they can learn more from. Twitter is used simply as a way of connecting with a wider audience; it is probably the least necessary of the social media widgets.

In the images below you can see that Twitter is the only social media widget available through the U-hosted version of the site. I was hoping that I would be able to add plug-ins and themes through the hosted version, but these functions seem limited to the upper level site administrators.

I have also highlighted the “Tag Cloud” widget, available in both versions, that I think is useful for organizational purposes. The one thing that was available and automatically included in the U-hosted version was the “Translate” widget which is handy, but not strictly necessary.

(A note on the “sort of” Pinterest widget: There is no Pinterest widget on the free WordPress.com version. I tried embedding the widget codes that Pinterest will generate for you, but, as they use java, they wouldn’t work. Luckily I found a site that tells you how to turn the Flickr widget into a Pinterest widget and a site that provided the html code to add a Pinterest follow button via a Text/Html widet.)

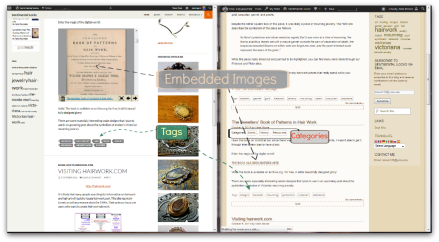

The other side of the decisions between the two versions of the site boiled down to mostly aesthetics. I prefer the themes available through WordPress.com, despite the lack of customization available for free, because they feature better fonts, neater layouts, and better integration of media.

In the images below I have highlighted some of the features that really sway me in the direct of the WordPress.com version. Pure aesthetics wise, the theme fonts are better, the layout feels like there is less wasted space on the tops and sides of the page, the tags on the WordPress.com version are stylized tags, rather than just text, etc.

The images I attempted to add in the U-hosted version sometimes resized themselves very strangely and skewed the proportions. The image of the diadem in the first screen-cap above had to be resized through the html code because it wanted to be taller than it was wide, opposite of the original proportions of the image.

You can also see that while I was able to directly embed an archive.org book viewer on the WordPress.com version, the same would not work in the U-hosted version. I tried various workarounds, but eventually just settled on providing a link to the book.

The U-hosted version does list the categories each post is filed under at the top of each post, which is nice.[edit: I just noticed the categories are also on the WordPress.com posts so this is basically a moot point.] This isn’t really necessary anyway, because the menu on the WordPress.com version scrolls with the viewer to provide easy navigation to any of the same categories. Indeed, the menu overall in the WordPress.com is much more dynamic.

I’m sorry Zoidberg! It’s not my fault, cut me some slack…

So, that’s where I’m at now. I’ve mostly settled into the WordPress.com platform, but I do plan to cross-post on the university hosted version as well.

Now that I’ve added a few posts and set up all the social media accounts, feel free to stop by and take a look!

WordPress.com – http://hairworkhistory.wordpress.com

University Hosted – http://clas-pages.uncc.edu/hairworkhistory/

Twitter – @hairworkhistory

Pinterest – Sentimental Locks / hairworkhistory@gmail.com

Flickr – Sentimental Locks / hairworkhistory@yahoo.com

Please share your comments/thoughts/suggestions in the comments, I would love to hear them!

“The Future of the Library in the Digital Age? Worrying about Preserving our Knowledge” by Ian Milligan

Ian Milligan, a #twitterstorian I’ve been following for a while now, has written a new article for ActiveHistory.ca discussing some of the issues that have been raised in our course. In response to the CBBC’s discussion “What’s the future of the library in the age of Google?”, Milligan considers the significance of such discussions for historians.

How are we currently preserving digital resources? What might we be losing with our current methods of digital preservation? Milligan points out that the idea that all things digital last forever is an illusion; we have little of the early web remaining now.

A very interesting read with some though-provoking points, as always.

Check it out HERE.